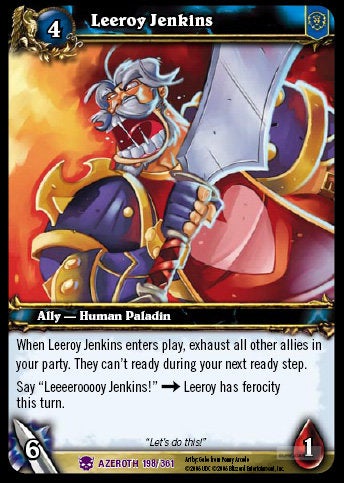

World of Warcraft celebrated its fifth anniversary last week. On 23rd November 2004, Blizzard launched its MMO in North America. Even though some critical features (player-versus-player battlegrounds, for one) weren’t implemented, the game clearly outstripped established rivals in polish and scale at launch, and demand was so intense that Blizzard’s overloaded servers spent the first few months fighting a losing battle against the tide of players. So you can hardly call Blizzard’s first steps in massively multiplayer gaming tentative. Nevertheless, WOW in its early days was a shadow of what it has become over the last five years, in terms of the quality of the game itself as well as the size of its player-base (two million in June 2005, 12 million today) and its impact on popular culture. You can trace that journey on this site: in the news and in reviews (the original 8, the re-review 10, the reviews of the Burning Crusade and Lich King expansions). Best of all, you can hear the story of its development in the words of its developer, in parts one and two of our exclusive Making of World of Warcraft. But some of that story can only be understood, and properly put into context, in hindsight. You’d need a book to comb over the significance of every event, so below we single out one development in the game and one in real life [“IRL”, surely -Ed] for each of WOW’s five years of operation. Some of them are famous, some obscure; it’s not a definitive list and they might not be the single most important moments in WOW’s history, but they all say something about where the game has been, how far it’s come, and how much it’s changed the gaming landscape. It did. On some servers, players exploited teleportation to carry Corrupted Blood from Zul’Gurub’s remote jungle location to the game’s major urban centres. It spread like wildfire, killing lower-level characters in seconds. Regular gameplay was completely disrupted; some players took malicious glee in spreading it, while others formed an impromptu relief effort, taking it upon themselves to heal the sick. Eventually, Blizzard was forced into a hard reset of affected servers to kill it off. The Corrupted Blood plague has since been used as a study on the spread of real-world epidemics - which it closely resembles - and has even invited comparisons to terrorism in the way some players chose to spread it. It was such a dramatic event that Blizzard sought to replicate it, notably with the zombie plague that heralded the launch of second expansion Wrath of the Lich King. But truth be told, it was the first and last time that WOW’s world of Azeroth would really take on a life of its own. Stories like this are more closely associated with less regulated “sandbox” MMOs like EVE Online. Blizzard, ever the control freak, the meticulous director of player experiences, might have sought to mimic Corrupted Blood under controlled circumstances, but it could never allow it to happen again. The fix was in. From now on, World of Warcraft would only run as its makers intended. Caught on video and posted mock-seriously on WOW’s forum, the moment spread first across the game’s community and then beyond it, and eventually escaped the confines of the internet and into national and international media. Leeroy became a sort of folk hero of WOW. His name and idiotic feat are immortalised as an in-game achievement and title; his image is recreated alongside Warcraft’s heroes and villains in the WOW trading card and miniatures merchandising; the player behind him, Ben Schultz, does public appearances at conventions. Looking back, the video’s wild popularity isn’t that easy to explain. It’s funny in a dumb sort of way, but fairly deeply entrenched in the arcane vernacular of raiding. Then again, you don’t need to understand how WOW dungeons work to understand the enormity of his mistake, his gung-ho vigour, or the fact that he’s having fun and not taking the game too seriously. Schultz did Blizzard an incalculable PR favour, not just in terms of exposure, but in demonstrating that WOW could be about friends messing about rather than nerds obsessing over detail. To this day, the most famous WOW player character isn’t a successful guild leader or elite PVP hero, but a chicken-eating village idiot just like the rest of us: a common man. It wasn’t long before they reached their apotheosis. Naxxramas was a 40-player raid, introduced in patch 1.11: Shadow of the Necropolis in June 2006. This floating city of the dead was an epic that raised the bar for multiplayer RPG design so high that even Blizzard has struggled to match it. The 15 boss encounters - neatly organised into four wings and a central, two-stage climax - were as intricate, varied and memorable as anything in a Zelda adventure or a Treasure shmup, only co-ordinated for co-operative gaming on the grandest scale: the square-dancing of Heigan the Unclean, the multi-tasking of the Four Horsemen, the panicked siege warfare of Kel’Thuzad. The problem was that only a tiny fraction of World of Warcraft’s huge audience got to see inside Naxxramas, let alone best it. In its original form, Naxxramas was as difficult as the game has ever been, and had the most stringent requirements of guild organisation and gear. It simultaneously proved how great MMO raiding could be, and how exclusive, intimidating and inaccessible. For its developers it was both climax and anti-climax, and they would never make another 40-man raid. Blizzard has progressively lowered the bar for raiding until Naxxramas itself was reborn as an “entry-level” raid for 10 or 25 players in Wrath of the Lich King - a stroke of populism that some players still bemoan, but that has probably changed the elitist structure of MMOs for good. Blizzard’s stock response to this sort of close-to-the-bone ribbing could be - still can be - defensive and frosty. But Parker and Stone’s barbs were welcomed with open arms, access to the game’s assets, and even an opportunity to use Burning Crusade alpha servers as a virtual film studio for the episode’s lengthy in-game sequences. It’s hard to know whether Blizzard was exercising corporate cunning or simply succumbing to a kind of inverse flattery - if you’re going to be mocked, it might as well be by the best, on the biggest stage - but either way, it was a PR masterstroke. It didn’t matter that Make Love, Not Warcraft - aired in September 2006 - was deliberately offensive and inaccurate. Parker and Stone clearly knew their subject and were treating WOW with their own unforgiving brand of affection, one that players could easily recognise and identify with; and they were comfortable enough with gaming subcultures to use the same “machinima” in-game animation techniques as the parodists in WOW’s own community. It was a cultural validation that ranked the game alongside presidents and pop stars in South Park’s gallery of targets. (Oh, and it was half an hour’s airtime, an Emmy award and a free trial in the DVD box-set, too.) Patch 2.3: The Gods of Zul’Aman was an excellent, well-rounded update, with sought-after features like a new 10-player dungeon, guild banks and speeded-up levelling in the game’s lengthy and rather disorganised mid-section. Part of the improvements to this portion of the game (usually the most neglected part of an MMO, while introductions and endgames are constantly revised) was an experimental overhaul of a backwater questing zone, circa level 40, called Dustwallow Marsh. The unassuming remake, centred around the new goblin hamlet of Mudsprocket, didn’t just add 50 new quests where they were desperately needed. It showed just how far Blizzard’s craft had come when it came to making solo storylines, not just since 2004, but since The Burning Crusade just months before. Eventful and varied pocket adventures - quest chains with satisfying arcs, loaded with pathos and humour, strangeness and spectacle - meandered and interlocked around the small zone in an exquisite pattern. Once you started there, it was impossible not to do all of it. A year later, we’d get an entire expansion made to this standard, but even that wasn’t the true significance of the new Dustwallow Marsh. At the time, Blizzard casually hinted that it would consider similar overhauls for one or two more of the original game’s zones. In fact, it would go on to announce that it would do the same, and more, for the entirety of the two original continents in 2010 expansion Cataclysm - a bold revision for which this revamp was surely a proof-of-concept. Blizzard getting its name on the door was a sign of just how far into the stratosphere of the games business WOW had propelled the closeted, perfectionist developer. If any questions were raised at this apparent hubris, they would be answered bluntly by the company’s balance sheets. Analysts estimate that WOW alone contributes half the super-publisher’s earnings, eclipsing even Guitar Hero and Call of Duty. It certainly rakes in hundreds of millions of dollars a year in subscriptions and sales - the PC Gaming Alliance reckons it could be as much as $1 billion a year. It was an audacious land-grab by Activision, a specialist in the retail-driven console market that had, at a stroke, snapped up the biggest player in online and PC games. Bobby Kotick boasted that it would cost a billion dollars to take on his prize goose and its golden egg. But at the end of the day, it meant more to him than it did to Blizzard. “In the time that Mike [Morhaime, Blizzard CEO] has been here, he’s had eight different bosses,” shrugged operational chief Paul Sams last year. “There’s a lot that we can learn from [Bobby]. And, candidly, there’s a lot that he can learn from us.” Blizzard had allowed “add-ons” or plug-ins since WOW began, mostly so the community could create its own interface utilities (often watched closely and then imitated by the developer in official updates). PopCap used this option to create a free version of its timeless puzzle game Bejeweled that players could run in a window while travelling around Azeroth, queuing for Battlegrounds, browsing the Auction House or performing some of the game’s more mindless chores. It later added a version of Peggle, too. Mini-games-within-a-game are nothing new, and there are far more popular and important add-ons available than Bejeweled - QuestHelper, for one, which wrote the rulebook on quest-tracking functionality, soon to be followed by Blizzard and all its rivals. But that an external developer would put one of its own properties within WOW indicated just how far beyond the stature of a regular game the MMO had grown. Valve’s Gabe Newell had argued that WOW had exceeded the parameters of a mere game to become a platform in its own right. PopCap proved him right. Glider was a popular “bot”, a program that could play the game for you, automating the process of levelling or grinding out gold. Like most MMOs, World of Warcraft’s basic design principle and the driving force of its economy is that time is (virtual) money - but since people’s time is valuable to them in the real world, virtual money ends up being worth real money, too. Hence programs like Glider which, reckoned creator Michael Donelly, sold 100,000 copies at $25 dollars a pop - some of them to individuals as well as to grey-market gold traders. Just another battle in the war on gold trading and power-levelling. Or was it? “Glider use severely harms the WOW gaming experience for other players by altering the balance of play, disrupting the social and immersive aspects of the game, and undermining the in-game economy,” Blizzard claimed in the suit, and few would argue with that. But the case hinged on an intellectual property argument that World of Warcraft was licensed to players, not owned by them. Blizzard may well have been acting with the majority of players’ best interests at heart, but the Glider case highlights a sad irony of MMOs: players’ personal investment in these games may be enormous, but their legal right to access them is frighteningly slender. As Tom Chilton revealed in the Making of WOW, splitting the game into Horde and Alliance factions was one of the most contentious decisions the developers made, but also one of the most successful. Deliberately antagonistic and bolstered by the powerfully characterful races, the divide - which even disallows communication between the factions, player speech being translated by the game into gibberish - gifted players with rivalry and pride and a sense of belonging, even if you had no friends and no guild. It deepened immersion immeasurably. You are either an Alliance person or a Horde person, and though you might roll a character on the other side to try its quests, you would never change. Which explains why the seemingly innocuous service that now allows you to move a character from one faction to another, changing its race in the process, attracts such ire. Despite the players’ complaints, it won’t destroy communities. It will probably only be used by a tiny minority. At $30, it’s too expensive to be abused. It’s an appropriate service to offer in a five-year-old game where your friends might have moved on. But, symbolically… it’s a betrayal of the game’s founding principles. The remarkable thing, of course, is that a computer game can get people so worked up about issues of cultural identity. For the Horde! In any case, the August 2009 event, the fourth, was as good a demonstration as any of the others - a better one, perhaps - of the remarkable relationship that’s developed between Blizzard and its fans: a relationship that existed before World of Warcraft, but that has been amplified and solidified by the game, and dragged out into the real world. As an entity, Blizzard can be aloof and over-protective. It would be easy to characterise the developer as a money-grabbing corporate bogeyman. But at BlizzCon, that mask doesn’t so much slip as vanish completely. Disclosure is total. Most companies announce a new game with an elliptical teaser trailer and, if you’re lucky, a screenshot. At BlizzCon 09, third WOW expansion Cataclysm was announced and then outlined in exhaustive detail across six or seven hours of developer panels and Q&As, and playable by the general public on hundreds of PCs. It’s remarkable that a single company with a limited catalogue can draw 20,000 attendees, sell internet and cable TV coverage, and dominate an equivalent floor space to the entire Tokyo Game Show. But maybe that narrow focus is the point; from unity comes strength, and in the roar that greeted Cataclysm (or Ozzy Osbourne, or house band Level 80 Elite Tauren Chieftain) the crowd spoke as one. BlizzCon is attended by none of the tawdry awkwardness of any other public (or even trade) games event. It’s silly, and it’s geeky, but no-one else there could possibly mind or care; and the height of silly geekiness, the costume and dance contest, is also a genuinely uplifting expression of community spirit. Games may still be perceived as a destructive and antisocial pursuit, but at BlizzCon 2009, one of the most derided of them all - World of Warcraft, the breaker of marriages, the sucker of young souls - showed what a great social bond they can be. Here’s to the next five years.