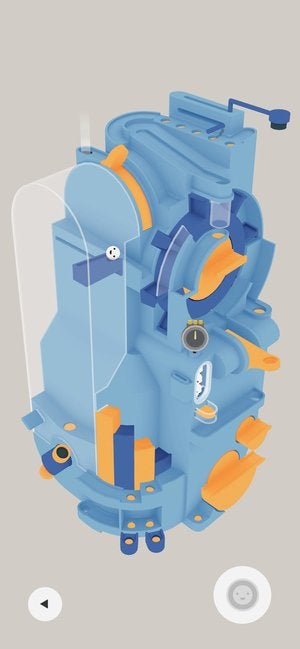

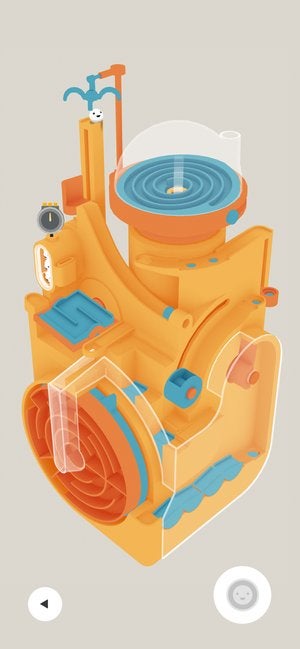

Whatever it’s called, I suspect we spend a lot of our lives chasing this moment. A moment that in games is often accompanied by the crunch and twist of a key in a lock, unseen gears moving, unseen parts turning and clicking into place. Welcome, then, to Automatoys, which gives you this moment every few seconds, it seems, without the moment ever seeming cheap or unearned. The instance of the fingerpost? Here is a field of fingerposts, and each one of them matters. Automatoys lets you lose on a selection of wonderful, complex, improbable machines. They’re little sculptures, really, characterful towers made of chunky plastic - I know the exact plastic, and after a few seconds playing so will you - and the objective is always the same. Put the coin in to release the little ball. Then move the ball from the start point to the exit, wherever start point and exit may be. How do you do this? You do this by understanding what the machine does, which means in these cases, understanding what the machine is doing at that moment. This is because these machines do a lot of things. You start down low, say, and a magnet swings by. You can attach yourself to the magnet, but what then? Stay on too long and you’re knocked off into the abyss. But maybe you can encourage something to knock you off earlier. Maybe you land near a sort of Archimedes screw. Can you tilt the ground to slide you into that, and to get the screw turning and lifting you higher? Then seesaws? A grabbing hand? The flipper from a pinball table? Who knows. Pinball looms large here, and not just because of the immediacy, the Looney Tunes dance of cause and effect. It’s because of complex results from simply inputs. I think that the only input here is tapping the screen. That sends the ball bouncing from one spot to another, and tilts the maze panel, and turns the Archimedes screw. Tap and hold, actually. I tilt the phone, but I think that’s just my mind looking for more control. Tap and hold. That’s everything. And depending on where you are, something happens - maybe moving you forward, maybe moving you back. Maybe ruining a few minutes’ progress. When I play, I am extremely tightly focused on the specific area of the machine where the ball currently resides - the cog it’s currently rested in, the channel that it threatens to spill out of. I tap the screen gently to see what might happen, and then I try to work out how that’s going to help. I land somewhere new and I wonder what the colourful little hammer thing up ahead might do - and then I look above it and understand exactly what it does. Everything here is briskly mechanical - none of it feels faked. (Excellent sound design helps beautifully here, and selflessly, really, as it works so you don’t notice how ingenious it is.) You can always see the little plastic whatsit that pops up to force you out of the hole the ball has settled in, and you can probably imagine taking the machine apart and seeing the hidden parts beneath the visible pieces. This all comes together and creates that endless tip-tap of understanding. I get it! Now where I am? What am I meant to do here? Ahh! Ahh, how brilliant. When I watch someone else playing, I see that each tap of the screen does everything - each part of the machine turns at the same time. And then that machine is completed, and there’s a new machine, with new gimmicks and new ideas, new breakthroughs waiting to be made. Once a machine has been completed, the question arises - how fast can you do it, now you know it can be done? One, two, three stars fast? And onwards - a new kind of learning, I think. Weirdly, what this really reminds me of is the old PS3 era of cinematic games like Uncharted, where you were told you had freedom but really you were sent out into a world that was actually a lovingly built machine that would propel you through it with maximum drama and maximum sense of satisfaction - if you could hit your marks. But Automatoys is more honest, I think, more transparent. You see the machine, and you see the reality that you are just a ball bearing moving through it all, powered by the skill of the operator, sure, but mainly by the ingenuity of the people who created these magnificent things in the first place. In a way, it makes me look on those cinematic action-adventure games a little more kindly. I see the craft that the developers tried to hide, and I can enjoy the gaps between what they were hoping would happen and what often happened instead. But that’s a fleeting thought, really. Mainly when I play Automatoys I think about Automatoys. I think about getting that ball from the start to the exit, and when one machine is done, I cannot wait to see the next.