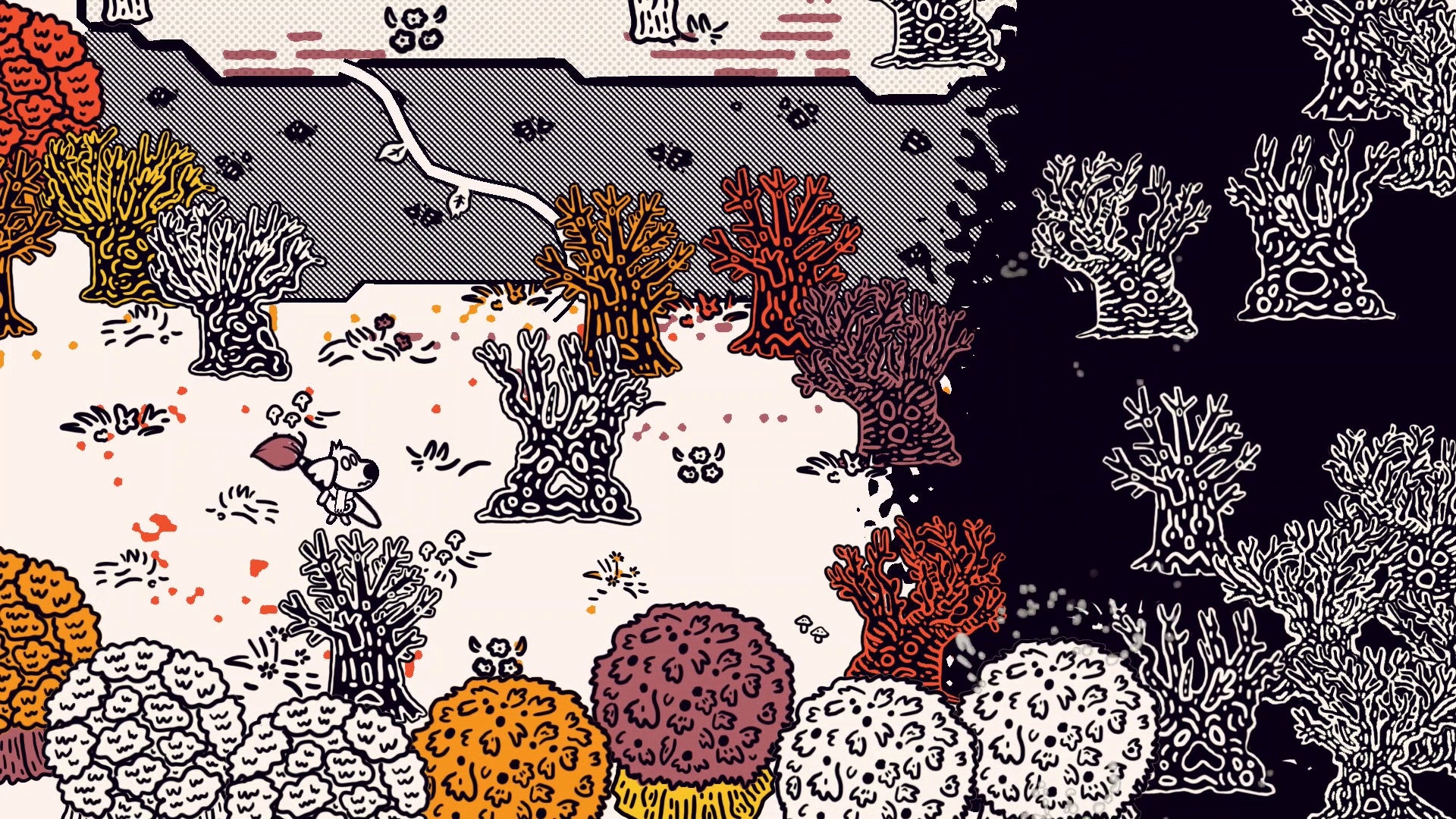

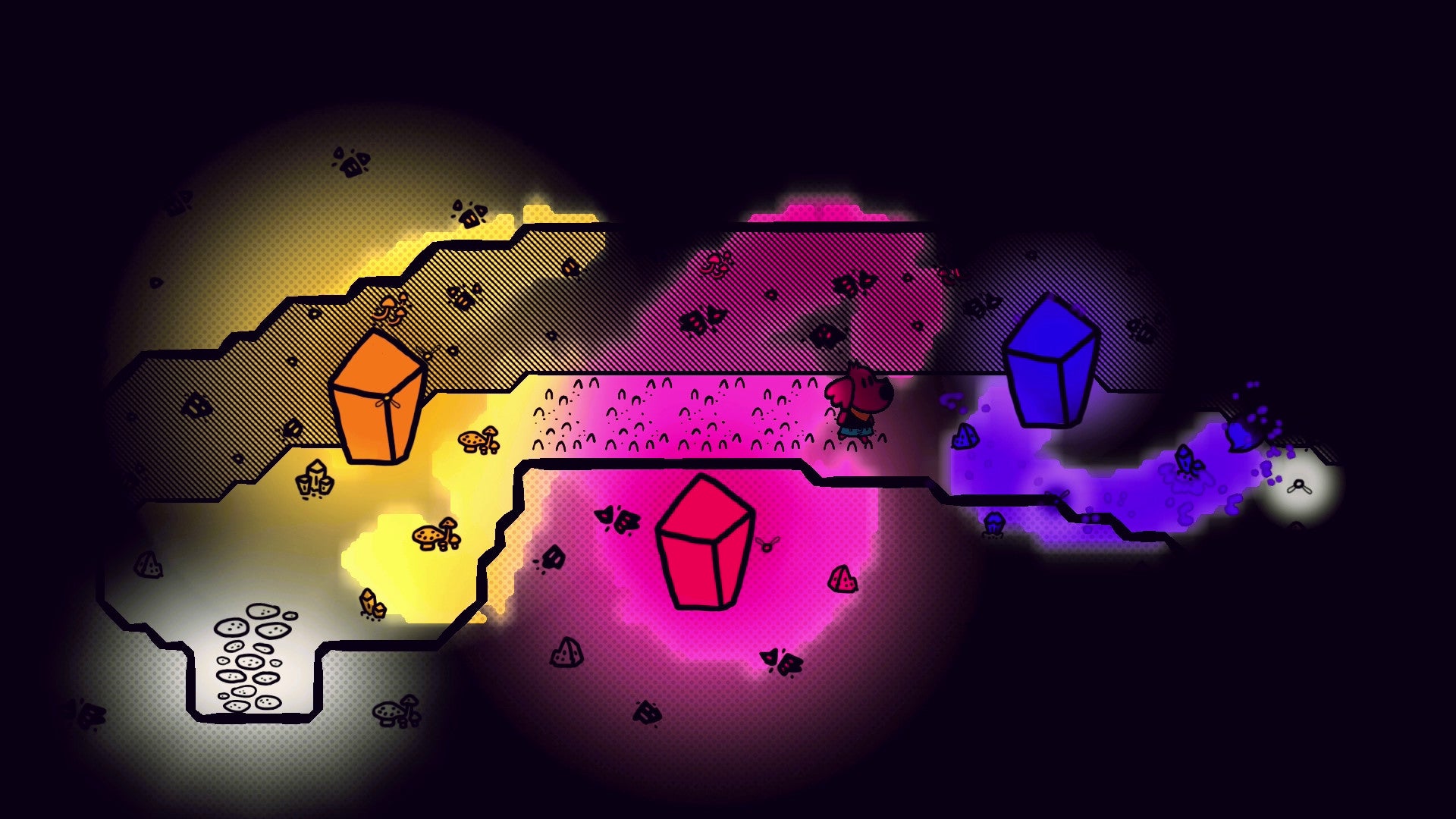

Chicory’s map is something you can draw on. And this brings the entire game, and everything in it, all together. It also gives it a lovely aesthetic. Thick black lines, white spaces and - swoon - print halftone with those brisk, stylish rows of dots. Snappy! In Chicory, you play a little dog whose world has been drained of colour. You take up the brush and mantle of the Wielder and your quest is to put things right. You fight bosses and solve puzzles, but you also tackle your own anxiety and feelings of inadequacy - are you right for such a big job? Do you have the gumption and the artistic talent to make it work? This allows for a lot of standard action-adventure stuff. You can use the brush to open up paths in a variety of ways, for example. You can paint vines to slide through them, or slip through little gaps. You can prod explodey things to blast open rocks with bursts of paint. You can fling yourself across gaps by tapping little flowery things with the brush. You can light up dark caves with swipes of bioluminescent colour. All lovely! But beyond this you have this game world, drained of colour, all black outlines and white spaces, and you’re very much free to do what you want with it. Sometimes, sure, you have to paint a specific thing. Sometimes one of the game mechanics will leave a burst of colour somewhere - when you’re blowing open those rocks, say. One particularly clever area very early on means you have to colour the ground to reveal secret messages. But for a lot of the time, you can simply paint or not paint. And this is the part of Chicory that has properly blown my mind. I have played this game slowly so far, and with big gaps in between. And I am also slapdash by nature and prone to laziness. So a lot of the early world of the game I left pretty much uncoloured, unless I really had to colour something in. Then I progressed further, and then, inevitably, I returned to the places I had previously been and I saw… the patches of colour I had laid down, waiting for me. The game had remembered. And in remembering, it was telling me something about the way I had played. I had started off and coloured pretty much everything. A few locations were dense with colours. I could also read the map to see the moments I worked out how to change colours, or change brush size, or brush shape - it was all laid out. When there were objects that reacted to colour I had toyed with them. When I was platforming, I could see where I had been flung across gaps by those magic plants - the spray of colour I left in my wake showed the ghost of my movements. I could see which areas I had returned to multiple times, because Chicory changes your base colours each time you come to a new screen, so there would be swipes and taps of previous journeys all waiting to be read. The most incredible moment, perhaps, was when I watched a trailer for the game after playing for a few hours, just to remember what I’d been doing and learn what might lay ahead. And I saw all these other ways of playing: people colouring in every single screen, using different brushes and colours to create features of the landscape where there were no features before. People testing the boundaries - the way the game will allow you to colour some objects with a single tap, or the way that the game sometimes stops you from going across lines. Chicory is dazzling. And the way it’s dazzling is something I’m increasingly interested in with games. Chicory is a Zelda-style adventure, sure, with lots of fun puzzles and dungeons and bosses, lots of stuff which is there ready-made and waiting for you to pick your way through. The people who made Chicory have stocked it with bespoke delights for you. But also, they have devoted a lot of the game to expressiveness - your expressiveness. You move with one stick and move your brush with another, knife-and-fork style, and it’s easy - if you’re a dummy like me - to not make the most of the brush. Or, for many more lively people, the brush becomes the whole world. A world to explore in the local co-op mode, even, or by ignoring the main journey and just drawing pictures and doodles. It ties into the game’s big theme, ultimately: how to deal with your own self-doubt and anxiety. You meet yourself on the page. You get to discover the way you express yourself afresh. All that empty space. Chicory’s blankness, waiting to be filled in, or not be filled in, or partially filled in, or subverted, is the key to the game’s quietly radical nature, I think. So yes, I guess Chicory is a bit like Zelda, but it’s also, fundamentally, unlike any game I have ever played.