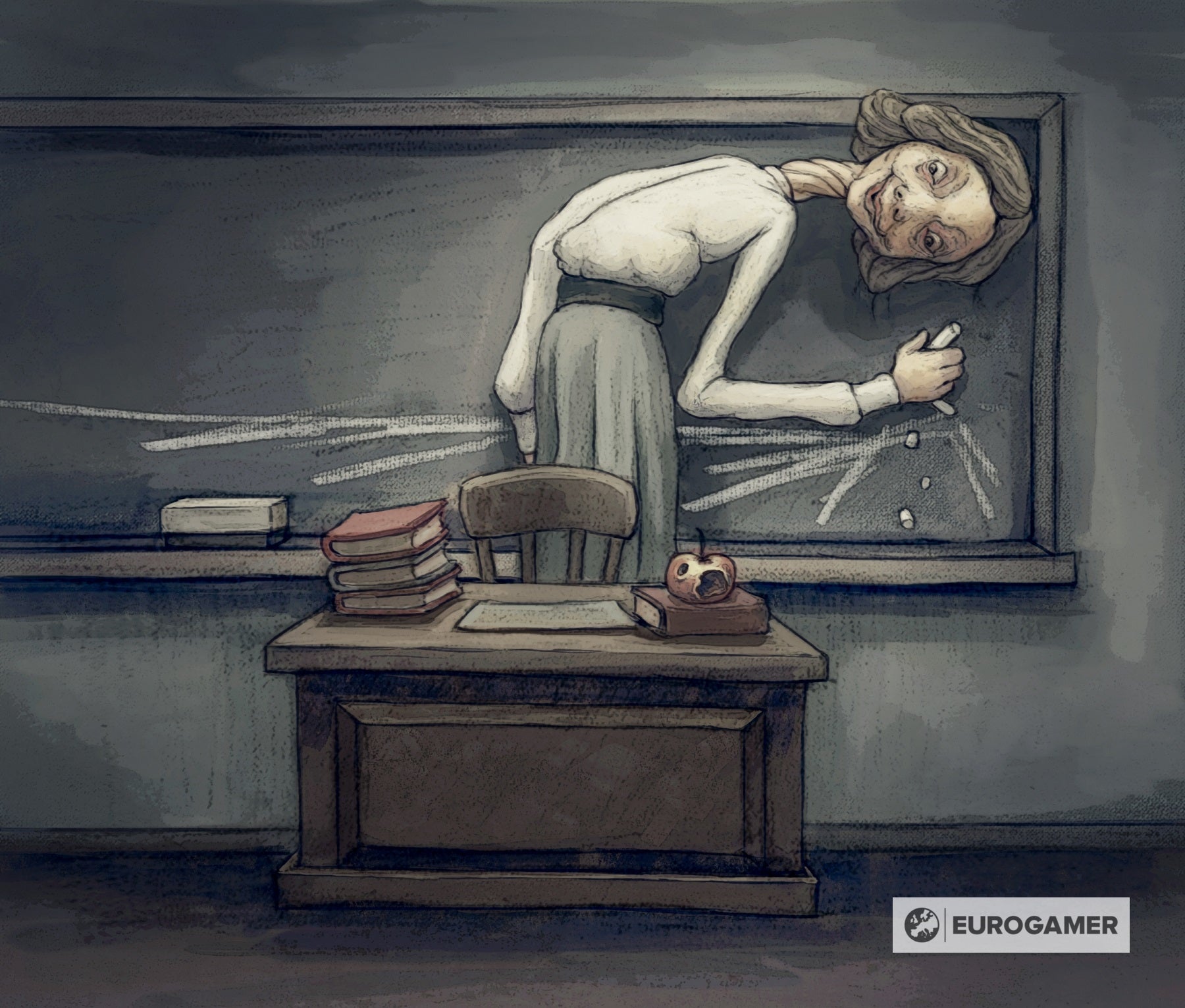

The long-awaited sequel is a little under two weeks away now (it releases on 11th February). I had a chance to play Little Nightmares 2 recently, and wrote about it. A demo was also released earlier this month for you to try. Did you? What did you think? Were you as scared of The Teacher as I was? I’ve been thinking about her, and about the game, since. I’ve been thinking about what it means for something to be scary, and how Tarsier manifests terror and frightens us. I’ve been thinking about fear. And I couldn’t think of a better person to ask about it than Dave Mervik, senior narrative designer on the game, and the person who dreamt a lot of the world up. What follows is our long and winding chat about the origins of the project, fear, formulas, and expectations. Let’s rewind the clock a bit, back to the beginning. Little Nightmares begins as an idea called Hunger, I think, back in 2015. Is that right? Dave Mervik: [Exhales loudly] It sounds correct! I’ll go with you on that one. I think it was, yeah. And Tarsier at this point - is that how you pronounce it, tar-see-uh? Dave Mervik: We hear many different variations on that. [Tar-see-uh] is what I say, so that’s right [smiles]. And Tarsier is working on Tearaway Unfolded for Media Molecule at the time. But in the background, something is bubbling away. Something dark, something a bit weird. Where does it come from, this Hunger idea? What was the original idea? Dave Mervik: That sort of stuff had been bubbling away a lot longer than Tearaway. I wouldn’t like to put the blame at Tearaway’s door [laughs]! Since the formation of the company, that stuff’s been bubbling away. And Tarsier is formed in - hang on, I read this on your website - 2004? Dave Mervik: Yeah. I had to write that on the website so we didn’t forget! I’ve been here over ten years now so all of these things kind of blow into one. But yeah, it was just a group of students back in the day, and you can see in the City of Metronome prototype that that mindset was there: looking at the world through skewed eyes. I don’t want to take too much of the interview with where it all came from, but it was the lifeblood of the company from the very start. A whole bunch of different factors just coalesced and came together, and ten years later, we got the chance to make the Hunger prototype. You mentioned seeing the world through different eyes. I’ve seen you mention that before. Is that a founding idea of Little Nightmares? Dave Mervik: I guess so. It’s just something that we naturally do. I don’t want to sound pretentious- You don’t! Dave Mervik: Damnit, I’ll try harder [laughs]! But it’s just the way we work. […] We’re talking about ideas that we care about, and this is all filtered through the theme of the game. In the first game was greed and consumption, and hunger obviously, and this [game] is escapism. One of the main pillars of Little Nightmares is how does a kid see the world? It’s one of the founding principles of this IP. How the kids experience the world in this very exaggerated fashion. So when you all first got together on Little Nightmares, then called Hunger, what was the original idea you had for it? Dave Mervik: It was a bunch of different original ideas. It was a camera system that the tech team had done some months before, which was called the dollhouse camera. And it was just showing how fun it was to rotate a building and then zoom into it and see something going on in there. And that just stayed there. And then a bunch of us were talking about the kind of games that we used to love, like Heart of Darkness and Flashback and Another World, which didn’t hold your hand but just dropped you into another world… literally [laughs]. […] Then the concept team started drawing things that really stuck with them. It was all these things. And suddenly, the opportunity came up for us to start working on a concept because we found out there were funds to be had. And, hang on, we could actually do something here because we were coming to the natural end of our time with Sony and [Media Molecule]. It was all of these things coming together. We were just really, really taken with this idea of a grotesque world and a child put in the middle of it, because [that] was something that really reverberated with us, something you can understand from our world. Of course it’s exaggerated and amplified and twisted by everyone that works on it but, still, the core of it is a kid’s experience, coming into the world and finding all these things that you have to adhere to, and these people who are in charge of you. And the world is not made for you. I say that all the time but it’s so important, that this isn’t your world. Do you think Little Nightmares 1 fulfilled what you set out to do with Hunger? Dave Mervik: Yeah. I mean, we couldn’t even believe we’ve got the chance to make our own game! It sounds a bit silly to say now, looking where we are, about to release a second one. But back then it was a pipe dream, almost like ’this is what we would do if we got the chance’. And so the chance to make something that demented? [This makes me laugh] Dave Mervik: But it was! We feel so fortunate that Bandai saw in it what we thought people would want, what people would be interested in. We always hoped; we obviously didn’t know. Because it is, it’s demented that world, isn’t it? But people get it. People get what we’re doing with it, that it’s not just there for shock value. It’s not just there to feel edgy or whatever. It’s about seeing the world and seeing the people that live in it, and expressing that in some way through these characters and these places you find yourself in. So of course it did. But you’re never happy, are you? You can always go back and do things differently, or better. And specifically, for us, it’s a nightmare - no branding intended - saying, ‘Okay take it from us,’ because we can’t let things go. You always want to go back and do it again, you can always do better. I want to talk about fear, about being scared. And this is quite a vague question but I’m interested to hear your answer. What’s your understanding of fear? Because I imagine you’ve thought about this quite a lot. Dave Mervik: Ever since I heard that’s what you wanted to talk about, I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it, because it’s a tough question, and I probably answer differently every time. But let’s get started, at least, with: it’s the stuff you try and forget about, or ignore, thrown right in your face as inescapable. This is my take on it. This isn’t the company standpoint by the way. You ask every single person in the company, they’ll give you something different. But for me, the things that I am terrified by are those things that you just can’t think about. I don’t care about vampires or zombies, or bleeding, because there’s so much of that, isn’t there, blood and flesh? And people go ‘what do you think?’ And I’m like that [shrugs]. I don’t care about what you’re doing there. I love David Lynch and find his take on what he does really interesting, because it’s how the subconscious tries to make sense of this stuff that your conscious self can’t cope with. Just mortality alone is something you… At least, we in the West are taught to just ignore, or cope with through religion or hedonism, or whatever. You just put your own mortality to the side as best you can. And when you’re faced with it, people can’t cope, because you’ve spent your life trying to run away from it. But more pertinent to Little Nightmares: something I looked into - and it scares me to say this was over 20 years ago! - [was] the idea of Carnivalesque. And what it did was revel in the grotesque, revel in the physical interior of people, the smells and the sounds and the things that go on inside your body, which nobody wants to see but everyone knows is there. Carnivalesque revelled in that. Some of the first clowns, that’s what they did. The ubiquitous comedy fart is everyone’s kind of pressure relief valve. Like ‘Oh yeah there’s things going on inside, but wasn’t that a funny sound!’ But when you see that through an endoscope, it’d be like, ‘Oh Jesus Christ. That’s not what’s going on inside me, is it? [But] look at me, I’ve got a cool hairdo, and look at my trendy t-shirt.’ It’s like everything is designed to make you forget what you really are. And I think the design of the Little Nightmares characters brings a little bit of that back. In this case, it’s your grotesque inner-self, the persona, that defines these different residents you see. It’s part of their outward appearance. There’s something about that that gets in that primal fear of this is a real, true ugliness. The Teacher, [which] everyone has really gotten into: this is how young kids experience what a teacher does, but it’s made physical. So there’s all these kinds of ideas, the things you try and wrestle with and make sense of. And that is a very very one-dimensional answer. There’s a million things to talk about. [We go on to talk about how far through the preview build I got. Mervik wants to know if I saw the Teacher playing the piano, and I did.] Dave Mervik: That, weirdly, is one of my favourite scenes. I’ve heard about this. I’ve been thinking about it. I’ve been wondering about it. Dave Mervik: [laughs] I like how it shows The Teacher as more than just a dumb monster who is put there to scare. Dave Mervik: I agree. And I wondered why you were doing that? Dave Mervik: It’s part of the balance of it that works there. One of the other things that works so well for the ratcheting up of fear in this game, is that it’s not just at ten or eleven all the time. It’s not like ‘quiet, quiet, quiet, jumpscare’, and then, ‘violence, violence, violence’. There’s this way it’s conducted, and it’s so important to how Little Nightmares works [that] you get these moments of quiet. That’s what I love about that scene. I don’t know if you would call it the mundanity of evil […] but it’s like this really quiet moment for this terrifying creature, just playing this piece [of music] that matters to her. I find that a really tense scene; I can’t take my eyes off it. And not just that I’m wondering if I’m going to get caught or anything. There’s just something about the lull that really works for, like, ‘What’s next though?’ You know what I mean? I really love that scene. Interesting you should mention the mundanity of evil. I was just watching a true crime documentary called The Night Stalker on Netflix- Dave Mervik: Oh about Ramirez? Really? Yeah, it isn’t an easy watch. But monsters are fascinating - well, this idea of monsters is fascinating. Because when, like you say, they’re put in front of you, there’s suddenly that mundanity about them. They’re not literal monsters, they don’t have fur and nails.They are, and they can only ever be, people, like us. And I think that’s perhaps more chilling. Did your approach to scaring people change in the sequel? Because it’s hard to scare people twice. Dave Mervik: [laughs] No it’s not. No, no, I don’t think so. We just had to take the scope into account really, because this is a bigger game. And also, it’s outside. You only saw outside twice, didn’t you, in the first game? At the end and when you saw the guests arrive. But that was all indoors, and so that feeling of claustrophobia and impending danger: you almost got it for free, in the subconscious at least. Whereas here, the very first thing you are is outside, so how do you make that still feel like you’re powerless and you’re not free? So we had to think about things in a different way. Little thing: I don’t know if they meant this but there’s so much imagery in the wilderness of being ensnared, trapped. The rope and the snare - literally, the snares: all these things that remind you about being prey, which I think is really cool. That kind of stuff that just seeps into your subconscious is really important. Is there a formula you use for scaring people? Something I noticed, and I really liked, comes from what you were just talking about: that attention to surroundings. Both the Teacher and the Hunter sections follow a similar kind of pattern, a kind of slow build up to the encounters with the characters themselves. You don’t see them for a while but the sense of them is all around, in visual clues and themes. Everything reinforces their presence, and it slowly builds to the eventual confrontation. Is it similar in every chapter - is that a formula you have? And are there ingredients you know you need in order to scare? Dave Mervik: There are certainly ingredients that we have. It’s not as clinical as a formula, though. We go off feel, and there’s a feel for what works that we’re happy with and we want to put out there. There’s a lot of love for things like Alien, the beginning of Alien. How long is that before anything remotely scary happens? It’s a bit like… Have you seen Hereditary? Dave Mervik: Yup. Yeah, that discomfort. I was literally just listening to Colin Stetson [who did the soundtrack] before we started talking, because I think anything that has his music on is a hundred per cent better and scarier [laughs]. Talking of music, you give a lot of space in Little Nightmares 2, don’t you? The music is quite- Dave Mervik: Tobias [Lilja] is crazy talented. We can’t tell him that to his face, though, or he might go somewhere else! So we keep his self esteem as low as possible [laughs].

Obviously, the Little Nightmares games: nobody talks in them, so there’s a lot of work done, storytelling-wise, particularly on the audio and the art side. When you’re playing through the Hunter’s shack, there’s so much prep-work done there to get you ready for what you know is coming. You know the kind of game you’re playing. The taxidermy hobby going on, the meat that he’s tearing, and the traps everywhere: everything [says] ’this is what we do to pray’. And guess what you are? All that is just there for you to get used to the idea. And even then, when it kicks in, you’re not ready. You say you go by feel with these things, but how do you know when something is scary? How do you know when you’ve got it? Dave Mervik: Ah! We play and replay and iterate all the time, with all of our stuff. So when you’re playing as a team, someone will say, ‘That’s not right is it?’ So you get little task forces [appearing]. ‘I know, if we do this, we can rejig this a little bit.’ And then, the week after, we play it again. [And] we play it again. And then the team knows. Ultimately it’s up to the directors to say ’this is how I want it to be’, but the team knows. I remember in the first game, I recorded… They didn’t know I was doing this, but they were playing a scene very early on in the development, and they were playing it together, and I heard people shouting and then laughing. I’m like, ‘Ohhh it’s going well,’ so I just recorded the audio of it and uploaded it to SoundCloud, as an ‘I think it’s going well’ [the track no longer appears to be there - I checked]. That’s how you know. […] We know what we’re trying to do, and we know when we’re there. […] You can’t do that going from a design document, to create fear from an equation. You have to go by feel. We’re talking a lot about fear and scaring people, and you’ve thought a lot about it because you’ve lived with it for the last five years. What’s it like working on a scary game like this, day in day out, a kind of unsettling game? Does it affect you in any way? Dave Mervik: Yeah I mean it does, doesn’t it? But you mustn’t forget you’re working through technical means, you work through Unreal, so it’s not like you’re sitting in a diorama for five years of your life. It’s not like acting in the way where you are in it as a person and it really affects you. But yeah, I am loremaster-general, so when I’m deep in it and all I’m doing all day is writing really, really dark stuff, or ugly behaviours, I come home bothered by that. But I think it will be different for the different disciplines. But you’re so focused on the job and achieving what you’re doing it’s, like I say, not so immersive. We’re just trying to do our job as best we can. It’s once you play at the end, you’re like, ‘Oh shit all that stuff came together really well, that’s cool.’ With release fast approaching, and best of luck with it, what do hope people will take away from the game? What are you really hoping people will see in it? Dave Mervik: We really want people to feel that this is a worthy sequel, that […] it’s not just a cash-in or whatever. It’s blown our mind how people have bought into this world. You always hope [for] it but you don’t expect it, that you put this thing out there and think, ‘Oh I wonder if people will engage with us because we’re taking a chance,’ you know, not talking and not telling people everything. People have bought into it in such a big way […] and they have all these theories and everything. I want them to feel that we’re respecting that and giving them something more to chew over, and that we care about it as much as they do. Thank you Dave Mervik, and thank you Bandai Namco for making it happen.