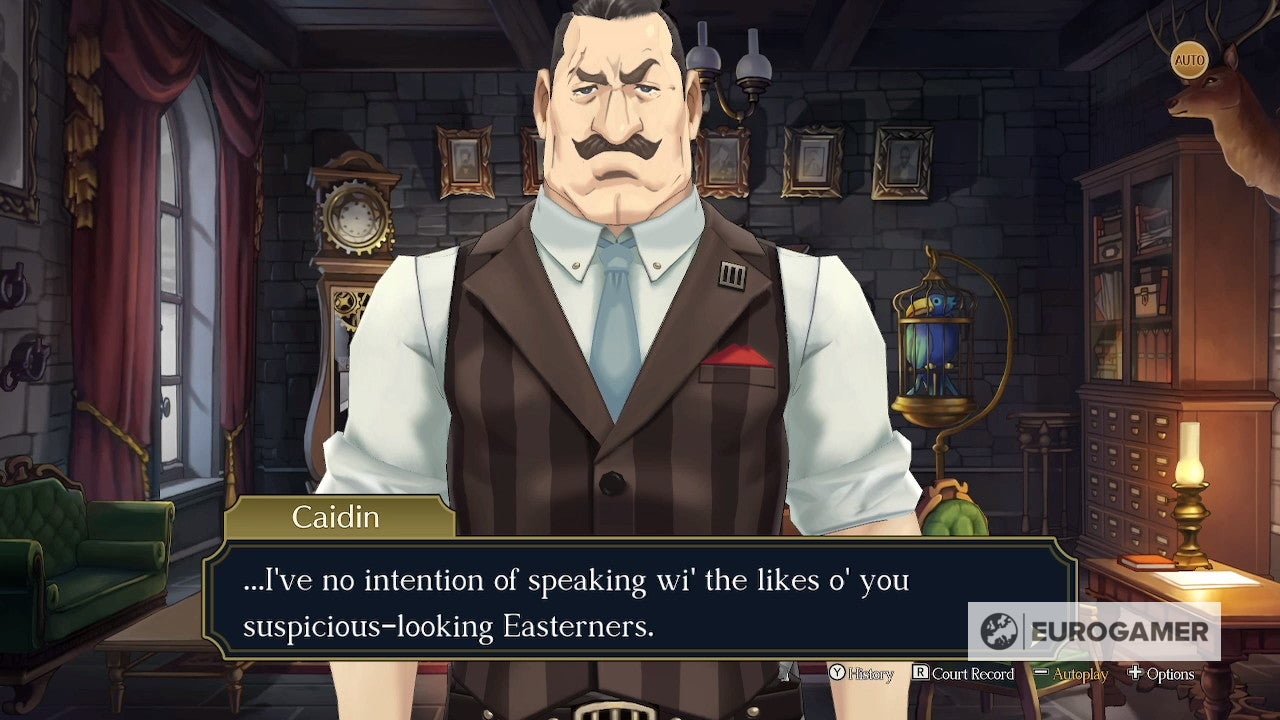

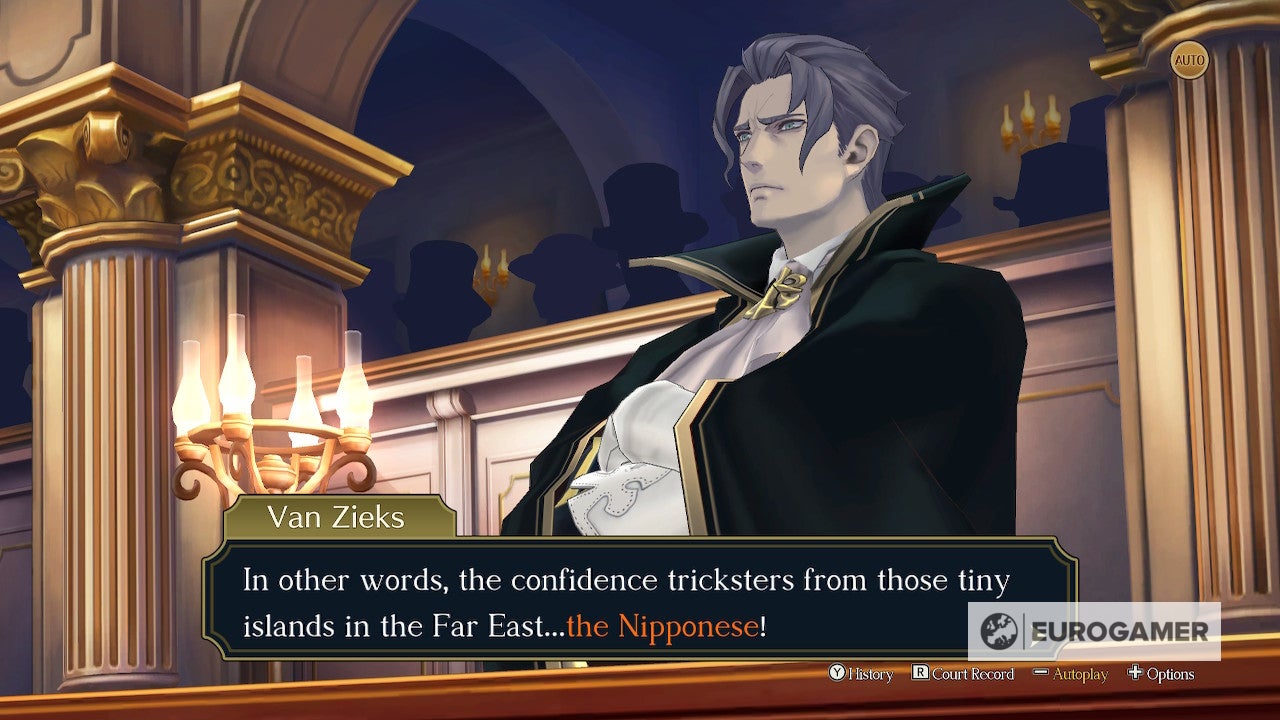

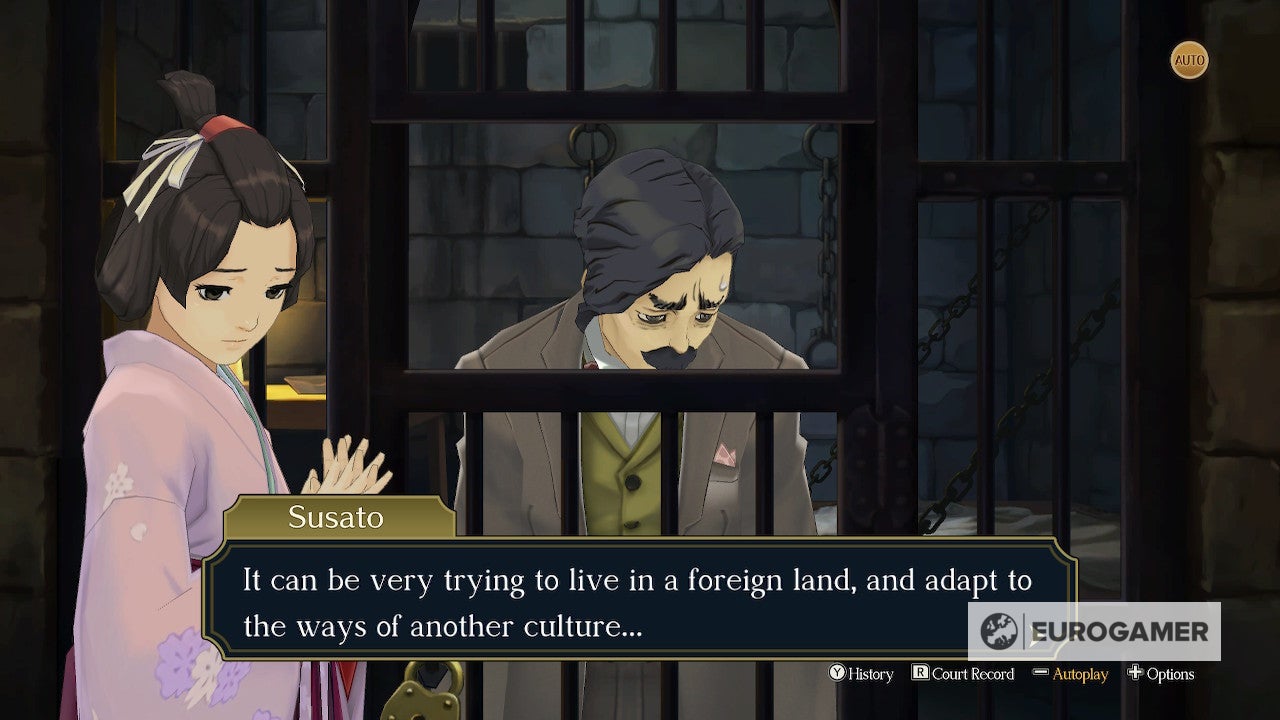

The premise of many games do, of course, involve journeying to new worlds. But even in the realms of fantasy or sci-fi, they can almost always be read from a Western, borderline colonialist, perspective. The term ‘immigrant’ itself comes loaded with connotations, especially considering Westerners who move abroad are referred to as expats instead. There have been immigration-themed games, such as the dystopian border controls of Papers, Please, or Bury Me, My Love and its human portrayal of the Syrian refugee crisis. As important as these examples are, however, their focus is more on the perilous process of migration, rather than what life is like for people in a new country, with different customs, where they’re in the minority. In Ryunosuke’s case, he’s a student from Japan who travels to England to learn from its judicial system, in the hope of transforming his own country’s legal system which at the time was still nascent to the concept of defence lawyers. Although this visit takes place within the context of a treaty between the two nations - based on the historic 1902 Anglo-Japanese Alliance, which did see a cross-cultural exchange between both sides - it’s clear the relationship is not really on equal standing. The implication is he is travelling to a superior nation - the British Empire was arguably the largest in the world in the Victorian era - and as such he is often treated as the backward Easterner and looked down upon by the British characters, despite being able to speak perfectly fluent English and have the rather respectable occupation of lawyer. That said, this imbalance is present even when the game is in Japan, such as in Ryunosuke’s first trial where an English witness initially refuses to ‘condescend’ to speak in Japanese - the kind of behaviour you might associate with Brits abroad (or people from other Anglophonic countries). But it’s felt far more strongly once you arrive in London to find how brazenly xenophobic people are towards both Ryunosuke and the “Nipponese”, which his prosecuting opponent, Barok Von Zieks, throws about with as much contempt as a slur. When Ryunosuke finds himself defending fellow Japanese, Natsume Soseki (based on the real-life moustachioed Meiji-era novelist), it’s almost shocking how much the defendant is singled out simply because he is Japanese, such as when one juror accentuates his “sallow complexion and short stature” as a sign of his guilt. You’d probably call it overbearing and exploitative if it wasn’t for the fact this is a game made by Japanese developers, and the original Japanese text is reportedly even more overtly racist. The prejudice and discrimination were certainly real at the time, when Western countries played up ‘Yellow Peril’ to stoke hate against Asian immigrants, even as they were happy to exploit them with unskilled low-paid jobs. Ironically, the lengthy wait for Great Ace Attorney’s localisation means its depiction of anti-Japanese sentiment hits a rawer nerve in 2021, when we’ve seen a spike in Asian hate crimes in the wake of the pandemic, from racial slurs to physical assault. It’s not just open hostility that’s captured but also the microaggressions, some of which might come off comical but still have the sting of reality when white people, whether wilfully or unintentionally, get foreign names wrong. That extends to when Ryunosuke and his judicial assistant Susato encounter Sholmes’ precocious assistant Iris, who immediately calls them ‘Runo’ and ‘Susie’ instead. While it’s true that she does give diminutives to her nearest and dearest, such as ‘Hurley’ for Sholmes, it still reflects the reality of how ethnic-sounding names are often anglicized for the benefit of Westerners. It may appear that the immigrant experience seen in Great Ace Attorney is largely a negative one, but there are positives too. We get to see solidarity between fellow countrymen, such as how Ryunosuke becomes the only lawyer willing to represent Sosemi, who himself has struggled with adapting to British culture, even before he finds himself accused of a crime. That solidarity is also expressed in the way the Japanese characters speak to each other privately in their native tongue, as denoted by the use of Japanese honorifics like “-san”, a deliberate localisation choice as explained by Capcom’s Janet Tsu in a fascinating Polygon interview. Perhaps what’s more interesting is comparing Great Ace Attorney with the previous, localised titles in the Ace Attorney series, because this also illustrates a part of the immigrant experience. Great Ace Attorney, despite almost remaining a Japanese exclusive, is now arguably the most faithfully localised entry of the entire series, whereas the originals were essentially Americanised (though still retaining some Japanese cultural references, including its legal system, resulting in fans often referring to the setting as Japanifornia), with protagonist Ryuichi Naruhodo renamed as Phoenix Wright. It’s as if they were sanded down to smooth out any content deemed ’too Japanese’. As such, they represent the pressure immigrants feel to assimilate into Western culture, at the expense of their own identity, in order to succeed. I know that, growing up, I often felt ashamed or embarrassed of my own Chinese heritage, and it wasn’t until after my teens I was able to find pride in my culture. I think it’s a similar experience people of other ethnicities have, wanting to fit into the culture they’ve grown up around, and only learning to appreciate their own roots later on (something I hope improves as diversity becomes more visible and meaningful in media). It’s a similar trajectory for the Ace Attorney series. That the latest games involve returning to the past to play as your own ancestor feels like the series coming full circle. It’s probably too much to expect a re-localisation effort to make the originals closer to their Japanese releases, but if series creator Shu Takumi ever decides to make a new, modern-day Ace Attorney title, I’d have no objections to the protagonist remaining, faithfully, as Ryuichi.