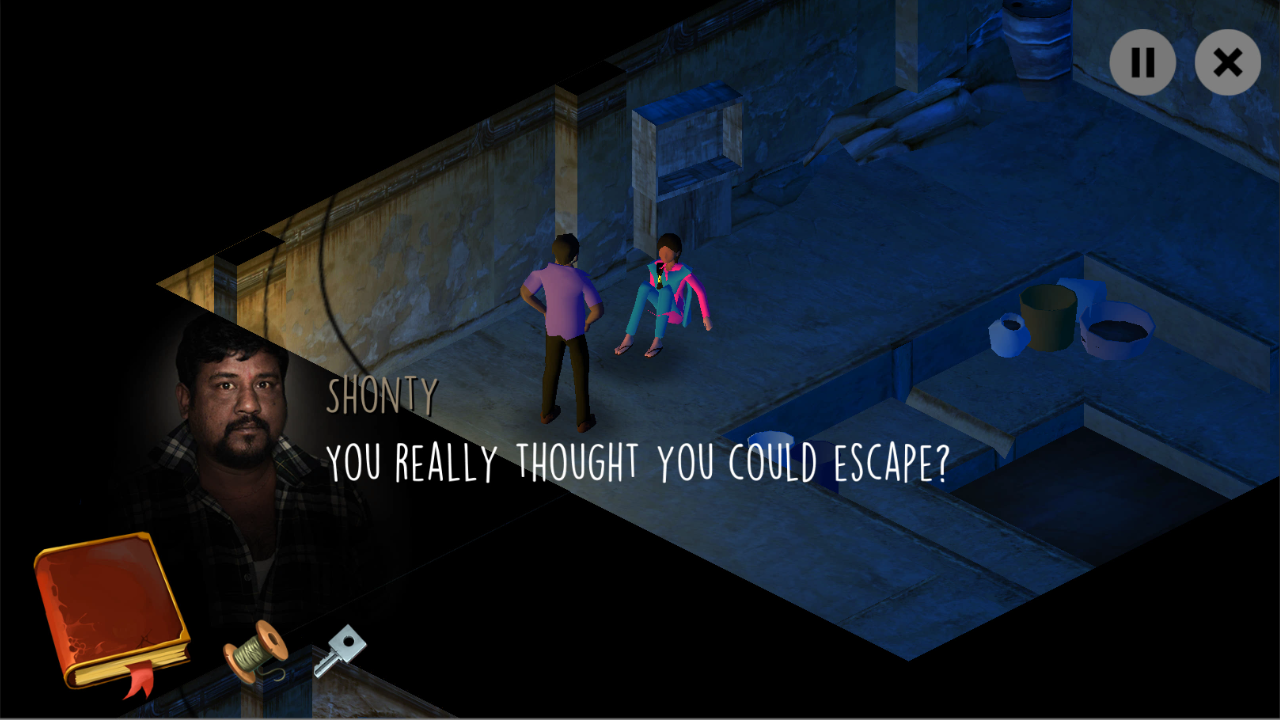

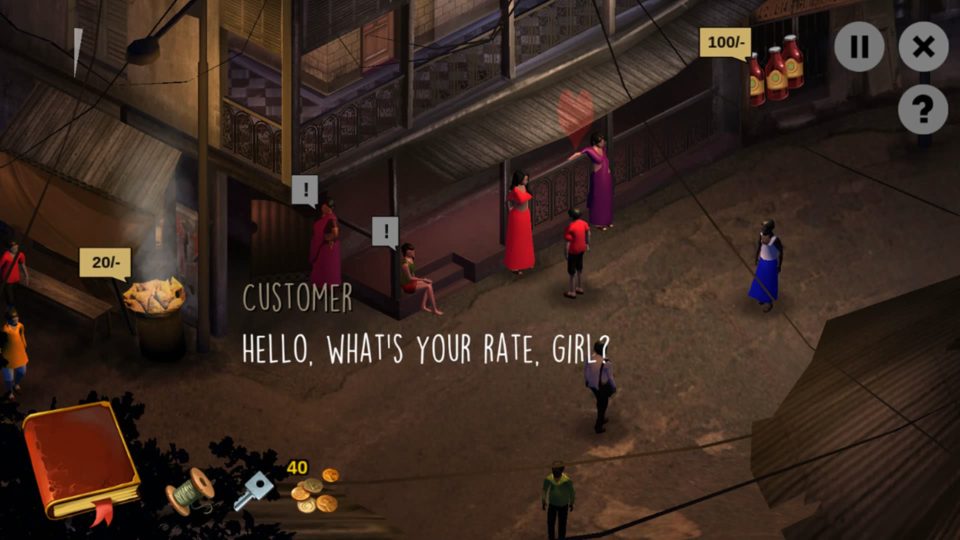

“In empathy for the millions of girls who disappear from the face of the earth.” -Missing: Game for a Cause, 2015. Leena Kejriwal is an acclaimed Indian photographer and installation artist with a passion for city life. “I love what shapes space, what shapes people, their history, their geography, their socio-economic structure,” she says in a video call with me. It’s a passion which took her into the heart of Indian cities with her camera time and time again. And it was on one such expedition, she found herself in a situation she would never forget. She found herself in a red light district, looking at girls too young to have any idea what they were doing. ‘Why were they here? How did they get here?’ she asked herself. And why was this being allowed to happen? These are questions Kejriwal would spend the next 20 years trying to answer, repeatedly revisiting red light districts all over Kolkata, talking to the girls there and trying to understand the challenges they faced. This work culminated in The Missing Art Project in 2014, at the India Art Fair, where her now iconic Missing silhouette was born. It’s a lifesize silhouette of a young girl designed to represent the millions of girls lost to the black hole of sex trafficking every day. India alone has more than 98 million sex trafficking victims, according to the Missing Link Trust website. 98 percent of them are female, and half of them girls. The Missing Art Project garnered worldwide attention, appearing in The Guardian here. And since 2014, the stencil has been used some 5000 times on walls across more than 40 cities, spreading both awareness of the issue and the lifesaving 1098 pan-India helpline for missing children. But Kejriwal wanted to spread the message further, and to do that, she believed she needed to go digital. It was while she was struggling with an AR app idea she came across Darfur is Dying and the idea of games for change. “And I said, ‘Whoa, I like this. I like what this game is doing,’” she says. A phone call later, she found herself knocking on game developer Satyajit Chakraborty’s door. Satyajit Chakraborty was a regular, work-for-hire developer in Kolkata at the time, turning out educational games or anything a client would pay for. To him, games were toys and entertainment, and he’d left the animation industry a few years earlier to pursue making them. Kejriwal’s proposition took him by surprise. She was direct: “I’m working on anti-trafficking and I want to create a game for change,” she said. He was stunned. “We were as surprised as you are right now!” he tells me. This went against everything he knew games to be. “No, no, no,” his mind was telling him. Games are for escaping reality, not returning to the darkest parts of it. Why would gamers want to play something like this? “But she was a little bit adamant on that,” he says, and she wouldn’t budge. Chakraborty went away to think about it, and it’s at this moment, something within him began to change. “I got into thinking, like, ‘If this is the last game that I had the chance to do in my life - this is the only game - then what will I do?” he says. With trepidation, then, he agreed. But it quickly became apparent he didn’t understand the subject like Kejriwal did. What he knew came from books and films, it wasn’t reality. “He never entered a red light district before so he had no idea,” Kejriwal says. So she offered to take him to one. “I took him into Bowbazar,” she says, which is one of the larger red light districts in Kolkata, “made him meet survivors, walk the streets of that area, which he had never done. He was really curious and he was looking around and really seeping [it] in and understanding it. “I remember him saying that it’s not what he imagined and it’s very strange for him. He’d never seen something like that before. For me,” she says, “I always knew because actually my childhood home was on the main road of one of the biggest red light districts of Asia. Since I was a kid, as a little girl, I’d heard of how little girls, or girls, are caught and put into that. So at that moment, probably, I was at my most vulnerable, like a seven or an eight year old. And I was quite a very frail girl, I was not a sporty kind, so I think I connected with that intense vulnerability so deep that for me that stayed with me all along, and that’s something that still stays with me. And that’s what I want to always reflect and show.” She also took him to the village area of Sundarbans where the highest number of trafficking victims come from. It’s about four hours away from Kolkata, near the Bay of Bengal, where the famous nature reserve and tigers are. These are poor villages away from the public eye where children disappear for money. But there are also survivors of sex trafficking living there who have managed to return home. It was one such survivor that Kejriwal took Chakraborty to see. Kejriwal told her why she was there - to try and authentically convey the plight of the people involved in an effort to help curb trafficking - and the lady was willing to help. “And when I asked her the first question, like, ‘So can you just tell us a little bit about what it was [like]?’ She froze,” Kejriwal says. “She froze. And this was after two years of her being back. She froze. And when I touched her like this [she gestures], she was cold. She’d become - her pupils dilated. I’m telling you,” she adds, “that scene, I can’t forget it at all.” Kejriwal told the lady it was okay and that she didn’t have to share anything, and got her a drink, and eventually she relaxed. “And when she started speaking, the first thing she said was, ‘I never knew that this could happen to anybody. I never knew that anybody would traffick or could take somebody away to do the kind of atrocities which were done to me.’” It had a powerful effect on them both. “It was mind blowing,” Chakraborty says. “It’s something I never expected and never dreamt about.” He realised he’d had no idea what was really going on. “None of the literature, movies or whatever, actually have done justice to the truth, because the truth is not palatable enough.” This is when things began to fundamentally change inside Chakraborty about what he thought the game should be. To make a game for entertainment and enjoyment would be to betray the truths he’d seen and heard, so he decided not to. He decided to put aside audience enjoyment in favour of authenticity, a hard world where people don’t win. “The audience can take it or not,” he says. “If I change the truth over there, I would be doing a disservice to these girls in a huge way.” So Missing: A Game for a Cause was born. It begins in a dark room. You, a girl called Champa (referred to as Ruby), have been abducted from your village, heavily drugged, and brought to a city to work in a brothel. You can’t remember your name or where you live, and the people who handle you are uncaring and vicious. Misbehave and they beat and rape you. You are forced into work the following day. It’s a world that breaks people. The only glimmer of hope comes from a broken girl there who tells you your name, and about a Missing silhouette she’s heard is sprayed on a wall nearby. On it is a number you can call, and perhaps if you can call it, you can get out. But it’s not as easy as it sounds. Only if you meet your daily income are you allowed a small window of opportunity to explore, and if you’re spotted in places you shouldn’t be, which are precisely the places you want to be, then you will be captured and taken back, and punished. Every day, your daily income target rises, and the windows of opportunity shrink and shrink. There’s a bit of dialogue choice and a bit of inventory management, and a bit of strategy in getting people drunk to earn more money from them, but generally the game is basic and a bit rough, and often frustrating to play - some of which is intended. Then again, it’s ambitious for a game made by mostly one person on a tight budget, and the niggles never dull the realisation the game comes from a place of truth. It’s a powerful thing to experience. Chakraborty really wasn’t sure how it would do. He certainly wasn’t encouraged after playtesters uninstalled the game, telling him they hated it. One woman chased him around a video game convention, shouting, “What have you done with it?! I am feeling so horrible with it!” he says, chuckling. But eventually, they came back, they reinstalled, and the more time they spent with it, the deeper the game’s reality sunk in. Eventually they asked, as Chakraborty and Kejriwal had hoped they would, “Really - this thing really happens?” The game was an unexpected success. It was released for Android and Apple phones in India in 2016, as that’s how people overwhelmingly play games in India - consoles and PCs are exorbitantly expensive so only a rich few can afford them - and it went on to win Indie Game of the Year Award at the NASSCOM Game Developers Conference 2016, something neither of the creators expected. But it was when the game launched in Bengali the following year, and was featured on the Google Play Store, it really took off, displacing the colossal Clash of Clans at the top of the gaming chart for an entire week. “Imagine that!” Chakraborty beams. Today, people have played it from all over the world. The highest numbers come from countries like Brazil and China, and South Korea and Indonesia, and it’s no coincidence. “These are countries which have a very high trafficking rate,” Kejriwal says. But for Kejriwal, the place she really wanted to impact was India. She wanted this game to spread awareness all over the country and so she pushed to have it translated into the Indian vernacular languages, something few other games have ever done. It’s now available in 12 of them. She also pushed for the game and movement to make it into schools, as the Missing Awareness and Safety School Programme. It’s still a relatively new project but has already reached more than a million students in India, though COVID-19 has stalled the work. Chakraborty and Kejriwal are also collaborating on a second game, a bigger game - a game that will fully realise the story of Champa from before she is abducted and to after. It’s called Missing: The Complete Saga and it successfully raised $50,000 on Kickstarter in 2017. They tell me it’s supposed to be out on PC at some point this coming year (it could come to console if a publisher picks it up). In addition to being a bigger concept than the original mobile game, it’s also a dramatically different-looking game, built out in full 3D with much more detail and more sophisticated lighting in order to pull you closer to the world Champa lives in. I had a brief go on an alpha build of the game and while I struggled a bit with the deeper simulation RPG aspects - it’s a bit clunky at the moment - it was undeniably a more eye-catching and ambitious game. However idyllic it may look, though, sex trafficking is still the backdrop to the game. In a sense, it’s hidden in plain sight, the threat of being captured potentially coming from anyone and anywhere. And more fieldwork has been done to accurately portray the reality, and more interviews have been carried out. This is still, beneath the RPG layers, a game for change. They have become a large part of Chakraborty’s purpose in making games now and something he’s given TED Talks about. Making Missing was something of an epiphany for him, he says. “What we’re seeing for video games is just the tip of the iceberg, and many things can be done and many things can be explored. We don’t get to there because of the fear of taking risks with those kinds of concepts.” “I would say it’s serendipity that I met him,” Kejriwal says. Their hope is that The Complete Saga will appeal to Western audiences. They are the people who funded it on Kickstarter and who they had in mind when designing it - a PC game is unlikely to find much of an audience in India. Perhaps they’ll be lured by playing in a part of the world they haven’t seen before, or perhaps they’ll be intrigued by the underlying cause. Whatever the reason, the goal remains the same: understanding and awareness. Sex trafficking is a global issue. It’s time a global audience was aware of it.