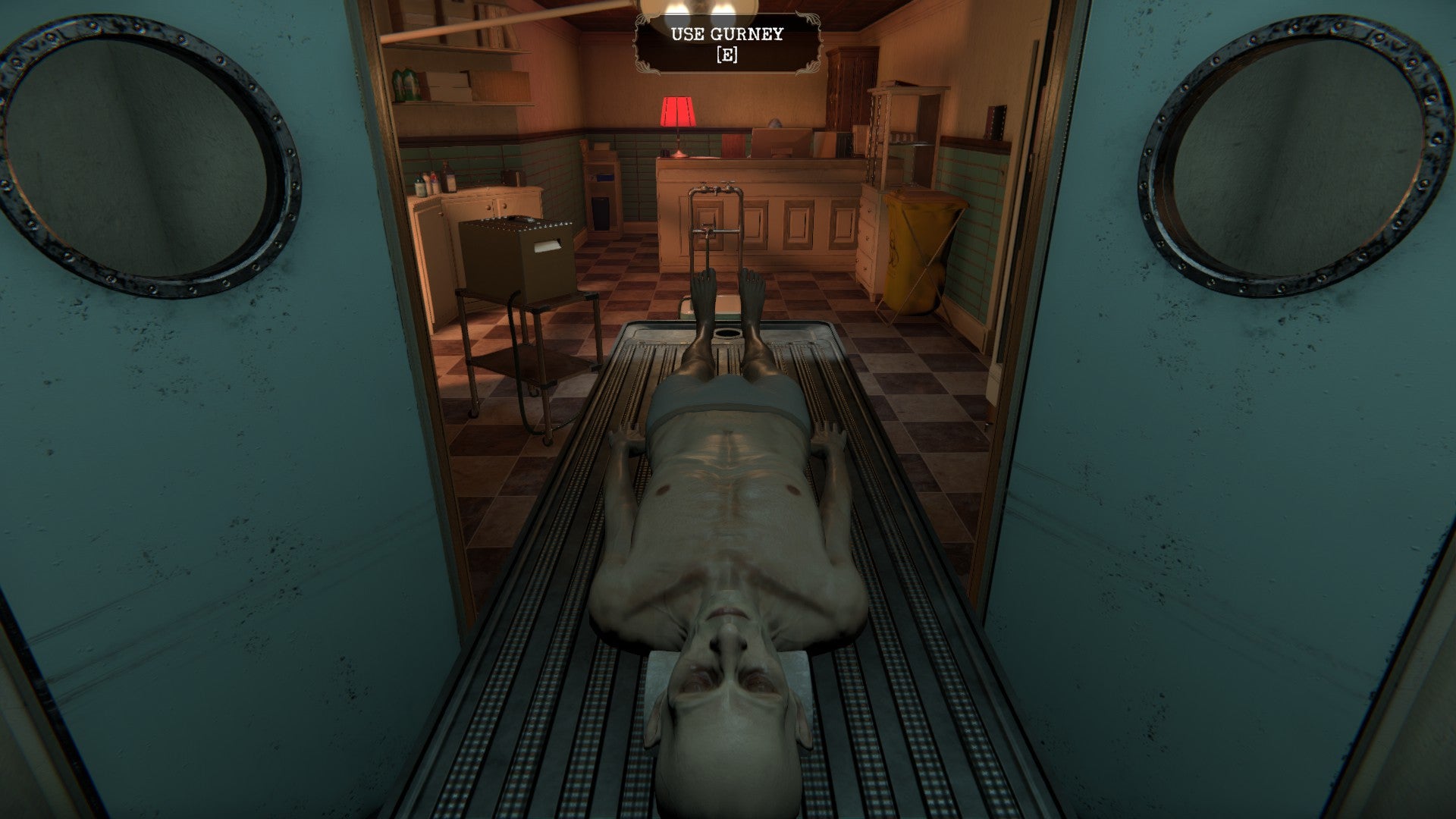

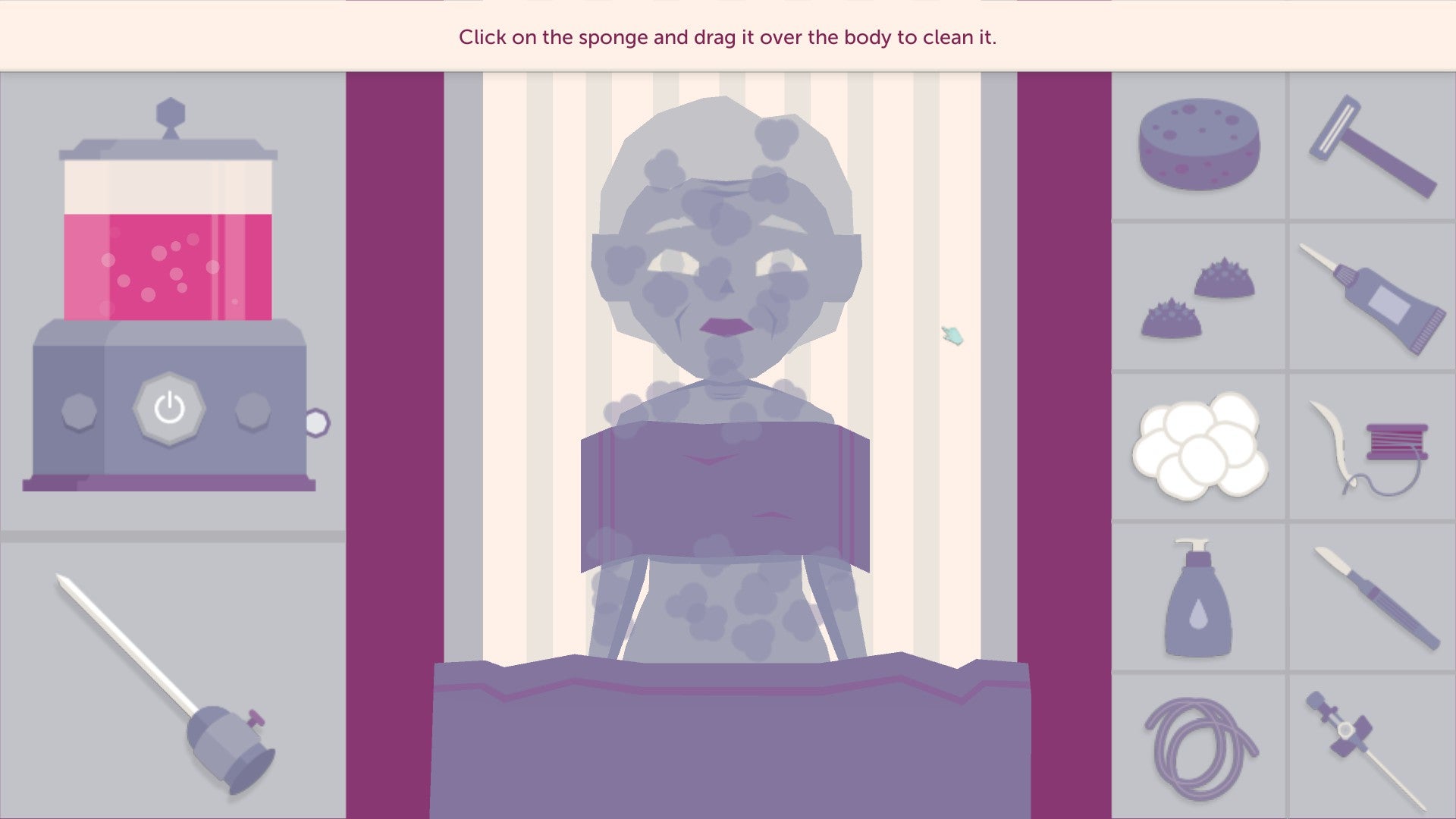

Morgues. All I have to do is write the word and it evokes a reaction. These places are steeped in our fundamental fears and preoccupations with death, and those fears and preoccupations are preyed upon by entertainment and amped up for horrors or police dramas. Chances are, you’ve never been in a morgue, but I bet you have an idea of what one looks like. I’ve been thinking about morgues this week because I’ve been in a couple and they made a strong impression on me. They’re not real, they’re in games, and the games are very much based around them. The Mortuary Assistant I’ve been working up the courage to play all week. It’s exactly what I feared a game like this would be: a horror. I’m a young lady who’s working a new morgue job when I’m locked in one night by my boss and told there’s a demon on the loose, and I don’t have to wait long before things get creepy and weird. Not that I hadn’t already freaked out seeing a cadaver on the table long before that. And then again when I had to give it the full treatment. It’s a gruesome job and the game delights in every step of it: pushing pins into gums so you can sew the jaw and mouth shut; cutting open the neck to put tubes in, and then pumping out the blood and replacing it with embalming fluid; emptying all the fluid from organs, and so on. Great backdrop for some scares, right? But what I didn’t expect to feel from it, and which definitely runs through it, was a sense of purposeful dignity in the work I was doing, returning dignity to the bodies I was working on. Death left them disordered and took control from them so I have to step in and reorder them. That’s why I’m closing their mouths and eyes, and removing the fluids, and cleaning them up, however barbaric it may seem. And even though there’s a demon loose, there’s a feeling of peaceful accomplishment and calm to it. It actually feels like a nice place to be. Chasing this experience with A Mortician’s Tale reinforces this. On the surface, the games couldn’t be more different: one is dark and ominous and photorealistic, and the other is gentle and bright with simple, storybook art and a carefully limited colour range. But underneath that, they’re absolutely saying the same thing - and you will know one from the other, which is a nice feeling. But A Mortician’s Tale has more to say, and it explains the whys of a lot of what you’re doing - why you put caps in the eyes before closing them, why you fill in the mouths. But more than that: it touches on the why of why people do this at all. Because there’s a stigma, isn’t there? Why would someone work with spooky dead bodies? What if they all came back to life and ate you? That’s the question brimming behind the surface whenever we think of someone in an undertaker’s role, however silly and ridiculous it sounds - thanks, movies. And if we meet someone who does: well, it’s notable, isn’t it? It’s unusual. Or how about noble? You see, the overwhelming feeling in A Mortician’s Tale is positivity, which was something else I didn’t expect. It’s in the small things like emails from your boss - “You’re a treasure, Charlie” has to be the nicest message anyone will ever receive - but also in the bigger picture of what you’re doing. Death is that icky thing many people don’t want to touch, but you will. You are prepared to step in, time and time again, and restore order at an unordered time - to prepare the body, yes, but also to prepare the loved ones emotionally attached to it for what comes next. It’s profound work. Two games about the same thing, one shedding more light on the other, and both shedding light on a profession often misconstrued or misunderstood. Morgues and morticians, you are not what I thought you were - you are more.

.jpg/BROK/resize/690%3E/format/jpg/quality/75/morticians_tale-(2).jpg)